THE PROMISE OF EQUALITY AND JUSTICE FOR ALL

by Tony Ball, Instructor of History

On August 25, 1864, over a year and half after the issuance of

the Emancipation Proclamation, a black woman named Annie Davis

wrote President Abraham Lincoln from Maryland. Her words remain

poignant to this day:

Mr president It is my Desire to be free. to go to see my

people on the eastern shore. my mistress wont let me you will

please let me know if we are free. and what i can do. I write

to you for advice. please send me word this week. or as soon

as possible and oblidge.

There is no record of a response from the Lincoln Administration.

Of course Annie Davis was not free; the Emancipation Proclamation

explicitly excluded those slaves that were in Union-controlled

territories, or in slave states like Maryland that had not joined

the Confederacy. As Lincoln had famously noted during the Gettysburg

Address, the American War for Independence had commenced some

"four score and seven" years earlier. But the American

Revolution, the long and sometimes violent struggle to make the

vaulted principles of the Declaration of Independence a reality

for African-Americans and other dispossessed peoples, was only

just beginning.

In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution prohibited slavery

in the United States. The 14th Amendment defined American citizenship

based on birth (not race), and guaranteed to all persons equal

protection and due process of law. The 15th Amendment forbade

states from denying citizens the right to vote based on their

race, color, or previous condition of servitude. With these Civil

War Amendments and Congress' Reconstruction program, there

was, for the first time in our history, a chance to bring about

a more racially just society. Less than a decade after the United

States Supreme Court had declared that no African-American could

ever be considered a citizen of the United States, the first blacks

were elected to the Congress, as well as to the legislatures of

the several southern states.

Like emancipation for Annie Davis, true progress towards racial

justice was elusive. For one thing, most white Americans in the

19th century simply did not believe in equality and were committed

to maintaining political, economic and social control over African-Americans.

In 1877, Congress officially ended Reconstruction, ordering the

withdrawal of the remaining federal troops from the south. Southern

whites were free to turn back the clock on equality and reverse

those gains that had been made by African-Americans in the years

immediately after the Civil War. Black voters were disenfranchised

and the legal, economic and social system refined to keep blacks

in virtual, if not actual, bondage. Jim Crow laws, mandating the

physical separation of the races, were vigorously enforced, and

those African-Americans who sought to leave the South for America's

Midwest and West often had to do so under cover of darkness.

Thousands of African-Americans like Annie Davis were only half-free,

completely subjugated and segregated in a society in which privilege

and skin color were inextricable. It would take two world wars

and an economic depression to bring the nation forward, and to

hold Americans to the ideals of liberty and equality that form

the foundation of our republic.

In 1910, the noted African-American sociol- ogist W. E. B. DuBois,

the anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, educational pioneer John

Dewey, and other progressives helped form the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Although just two

decades earlier the United States Supreme Court had declared in

the case of Plessy v. Ferguson that the forced segregation of

blacks was constitutional as long as they were given "equal"

facilities, the NAACP was committed to the strategy of using litigation

to widen opportunities and address racial injustice. Early victories

before the Supreme Court in the late 1910s and 1920s suggested

that the NAACP had embarked on the right course.

Meanwhile, African-American soldiers had served with distinction

during America's involvement in World War I (1917-1918),

and returned to the United States with greater expectations for

equal treatment and economic opportunity. However, the broader

society was still ill-prepared for meaningful advances in civil

rights. Indeed, after the production of the notoriously racist

film The Birth of a Nation in 1915, organizations like the Ku

Klux Klan experienced a resurgence, and African-Americans were

increasingly the victims of lynching and other forms of racial

violence. Indeed, even as black intellectuals and artists thrived

during the years of the Harlem Renaissance and as African-Americans

migrated to Northern industrial cities from the South in greater

numbers, racial violence and injustice became even more entrenched.

The American stock market crash in October, 1929, and the ensuing

Great Depression devastated African-Americans, who were disproportionately

employed in the hard-hit agricultural sector of the economy. However,

the Depression also helped forge a political realignment in the

United States in which African-Americans, long faithful to Lincoln's

Republican Party, were now part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's

Democratic New Deal Coalition. Together with intellectuals, Catholics,

Jews, poor farmers and organized labor, African-Americans were

part of a new progressivism in the United States which would redefine

American society and government's role within it.

Despite the importance of African-Americans to Roosevelt's

political coalition, little actual progress was made in the area

of civil rights during the 1930s. Roosevelt steadfastly declined

to endorse federal anti-lynching laws, and much of the legislation

aimed at alleviating the effects of the Depression excluded African-Americans.

When the United States' entry into World War II seemed an

inevitability, the African-American labor leader A. Philip Randolph

threatened a demonstration in the nation's capital to protest

unjust treatment at home. Roosevelt responded by issuing an executive

order which forbade government contractors from discriminating

in hiring or wages based on race, and Randolph called off the

march on Washington. As they had in World War I, African-American

soldiers, sailors and airmen played a crucial role in the second

World War, although again in segre-gated units. Significantly,

blacks and women were vital to the nation's wartime industries

which produced the munitions, planes, ships, tanks and other equipment

necessary in the prosecution of the war.

World War II forced Americans to look more carefully at their

own record on race and civil rights and further raised the expectations

of African-Americans. In 1946, Franklin Roosevelt's successor

Harry Truman created the Federal Committee on Civil Rights; two

years later Truman ordered the desegregation of the U.S. armed

services. Meanwhile the NAACP continued its litigation strategy.

When a black student at the University of Oklahoma was not allowed

to sit in the same classroom with white students, the NAACP filed

suit. The Supreme Court invalidated the University of Oklahoma's

segregation policy, ruling that forcing the student, G. W. McLaurin,

to sit in an adjoining hallway could not be considered equal treatment

as required by the 14th Amendment or the Supreme Court's

1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. At the same time, the Court

indicated its willingness to reconsider Plessy's "separate

but equal" doctrine altogether, and NAACP attorneys began

to envision an end to legally enforced Jim Crow segregation.

That opportunity came with the 1954 case of Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, Kansas in which Chief Justice Earl Warren

declared on behalf of a unanimous court that the segregation of

children in public schools solely on the basis of race violated

the Constitution's 14th Amendment, because "separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal." This ruling

was a major victory for the NAACP and for Thurgood Marshall, who

argued the case before the Court and would subsequently be named

the nation's first African-American Supreme Court justice.

However, getting southern states to adhere to the Court's

mandate would be no easy task and after the Brown decision the

civil rights strategy clearly shifted from litigation to political

activism and protest.

White resistance to desegregation was fierce. In the summer of

1955, a 14-year-old boy named Emmett Till was lynched in the small

town of Money, Mississippi, presumably for having said "bye, baby"

to a white woman in a candy store. Throughout 1955, local sheriffs

in the South stepped up the enforcement of Jim Crow laws and customs,

notwithstanding the clear direction of the Supreme Court towards

invalidating such segregation.

In Montgomery, Alabama, a 15-year-old girl black named Claudette

Colvin was arrested for refusing to give her bus seat over to

a white passenger. Montgomery's civil rights community considered

rallying to Colvin's cause but ultimately decided that Colvin,

who was unmarried and pregnant at the time, might not be the best

person to symbolize the pernicious effects of Jim Crow segregation.

Some months later, in December of 1955, a 43-year-old seamstress

named Rosa Parks was arrested by Montgomery's police also

for having refused to vacate her bus seat to a white passenger.

This time, the civil rights community in Montgomery mobilized,

forming a Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and calling

for a boycott of the city's public transportation system.

The MIA selected as its president a young minister named Martin

Luther King, Jr. and the modern civil rights era had begun.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted over a year. Although the practice

of boycott in America went back to the days preceding the War

for Independence, King and the entire MIA leadership were indicted

on charges of "conspiring" to disrupt the city's

bus system. Bayard Rustin, one of King's closest advisors,

urged the Montgomery boycott organizers to submit freely to arrest

following the non- violent principles of Mohandas Gandhi. The

adoption of passive resistance, and King's subsequent articulation

of principles of non-violence based on Christian theology, elevated

King as a moral leader and gave him national stature.

The boycott finally came to an end on December 21, 1956, after

the U.S. Supreme Court declared Montgomery's bus segregation

unconstitutional. But King was committed to taking the civil rights

agenda forward. He helped form a new organization, the Southern

Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), whose focus extended beyond

desegregation of transportation facilities to education, voting

rights, employment and economic opportunities.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower had succeeded Harry Truman in

1953. Eisenhower gave only lukewarm support to the Supreme Court's

decision in Brown v. Board of Education. However, he did back

the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first federal anti-discrimination

legislation since the end of Reconstruction. In 1957 Eisenhower

also sent 1,100 federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce

a federal court order mandating the admission of black students

to the city's Central High School.

In the early the 1960s, young people began to take a more active

role in the growing civil rights movement. Black college students

developed the strategy of the sit-in, aimed initially at forcing

the desegregation of local restaurants in places like Greensboro,

North Carolina. Student activism represented a new phase in the

civil rights movement as well as the beginning of the political,

cultural and social turmoil of the 1960s. In April, 1960 young

people met and formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

(SNCC). SNCC initially embraced nonviolent strategies but during

the 1960s its use of direct confrontation and increasing militancy

would stand it in sharper contrast with King and the older, more

conservative civil rights leaders.

In 1961, college students began partici-pating in "Freedom

Rides" in which interracial groups challenged segregation

aboard interstate buses and trains. When John Lewis, one of the

black riders and a future member of Congress, entered a Greyhound

station in Rock Hill, South Carolina, he was brutally attacked

by a white mob. The local police stood by and watched. That incident

and subsequent violence against freedom riders highlighted the

need for strong federal leadership. King and other civil rights

leaders appealed to President John F. Kennedy for support. But

Kennedy was hamstrung by his own party; southern Democrats constituted

a powerful bloc in the Senate and were committed to defeating

any additional civil rights legislation.

That reality led the NAACP, SNCC, the SCLC and the Congress on

Racial Equality (CORE) to focus their efforts on voter registration

and education in the South. Despite their differences, all of

the major civil rights groups began to view political empowerment

as a necessary precondition to further progress. But political

enfranchisement struck at the heart of the white power structure,

and led to escalating levels of violence and suppression against

civil rights activists. Alabama's state courts prohibited

protest, and in April, 1963, King was arrested in Birmingham for

engaging in a nonviolent march. From his Birmingham jail cell,

King wrote a famous letter which crystallized his philosophy and

energized the civil rights movement. Freedom, wrote King, "is

never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded

by the oppressed." The goal of nonviolent direct action was

"to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a

community... is forced to confront the issue."

That crisis had certainly arrived in 1963. In May much of the

nation and indeed the world was outraged when Birmingham's

police chief, Eugene "Bull" Connor, set his fire hoses

and police dogs on young children, assembled to peacefully protest

continued segregation and injustice in the city. This, and the

assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers in Jackson,

Mississippi, the following month illustrated the point that white

segregationists were willing to use terror and violence to stem

the tide of change.

In response to the violent turn of events, the Kennedy administration

proposed more sweeping civil rights legislation, but again this

effort was stymied by southern Democrats. A coalition of civil

rights organizations sought to support Kennedy's initiatives

by planning a new protest on Washington, 22 years after A. Philip

Randolph's threatened protest in the nation's capital

had been called off. In August, 1963, over a quarter million marchers

gathered before the Lincoln Memorial to hear King's dream

for a racially just society, in which people would be judged not

"by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

King's impassioned plea did not stop the racial violence.

Just two weeks later four little girls attending Sunday school

in Birmingham were killed when a bomb planted by white racists

exploded at the 16th Street Baptist Church.

After John F. Kennedy's assassination in November, 1963,

the civil rights movement took a new turn. Kennedy's successor,

Lyndon Baines Johnson, was committed to the civil rights agenda.

Moreover, as a former southern senator himself, Johnson had the

standing and political skill to effectively deal with the members

of his own party who had stymied legislation in the past. Johnson

engineered Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

made all segregation in public facilities illegal, established

an Equal Opportunity Employment Commission to combat job discrimination,

and banned gender discrimination in employment and education.

As Congress was taking up the civil rights legislation, activists

continued their voter registration and education efforts. The

major civil rights organizations targeted Mississippi for a massive

voter registration drive to begin in the summer of 1964. Mississippi's

"Freedom Summer" attracted scores of college students

from throughout the nation who braved racist local law enforcement,

the Ku Klux Klan and the hostilities of white mobs to enfranchise

African-American voters. The murder of three student activists

- James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner -

in June and a wave of church bombings, shootings and beatings,

did not prevent the organizers of the "Freedom Summer"

from empowering hundreds of black voters. However, the violence

perpetrated against the Freedom Summer activists, as well as the

escalation of the conflict in Vietnam, persuaded many young people

in the civil rights struggle that the time had come to abandon

the core principles of nonviolence and passive resistance that

King had popularized.

Moreover, the traditional civil rights focus on desegregation

seemed to ignore many of the pressing social and economic problems

faced by African-Americans outside the south. The once booming

industry that had attracted blacks to the northeast and midwest

were beginning to close, and America's central cities had

fallen into a rapid decline. The black nationalist and Nation

of Islam spokesman Malcolm X came to stand for a more militant

urban movement, which questioned the wisdom of nonviolence as

well as the emphasis on integration. Malcolm X's assassination

in 1965 did little to quiet this more strident activism. In 1966,

Stokely Carmichael became chair of SNCC. He moved to expel SNCC's

white members and to promote more militant confrontation. Even

the word "Nonviolent" in SNCC's acronym was changed

to "National," clearly indicating the new direction

the organization was taking. "Black Power" became Carmichael's

favorite slogan. H. Rap Brown, Carmichael's successor at

SNCC, declared violence "as American as apple pie."

In October, 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black

Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, California. The Party's

minister of education, Eldridge Cleaver, became one of the nation's

most eloquent and controversial spokesmen for the new militancy

which advocated the violent overthrow of repressive political

and economic systems.

Part of the problem was that after the passage of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and the subsequent 1965 Voting Rights Act, the goals

and objectives of the civil rights movement became much less clear.

King began to speak more clearly about issues of poverty and oppression

that transcended racism, launching plans to begin a Poor People's

Campaign in 1967. He also spoke out against the war in Vietnam.

But the issues of poverty and American policy abroad were far

more complex than dismantling Jim Crow segregation in the south,

and their solutions far more elusive.

To many, King's assassination in 1968 marked the end of

the traditional civil rights movement. SNCC was virtually defunct

by 1969 and most of the Black Panther leadership was either jailed,

exiled or dead by the end of the decade. There can be little doubt

that America still has a long road before (to quote King's

"I Have a Dream" speech) the nation rises "up and

lives out the true meaning of its creed." But the changes

which occurred in American society during the late 1950s and 1960s

were indeed profound, and moved the nation far closer than it

has ever been to fulfilling the constitutional promise of equality

and justice for all.

Tony Ball

Instructor in History

Housatonic Community College

December 27, 2001

|

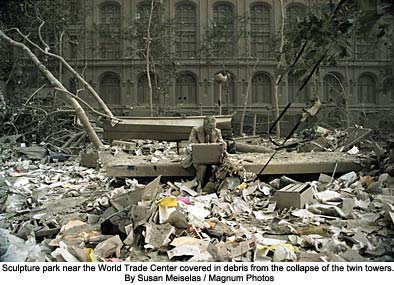

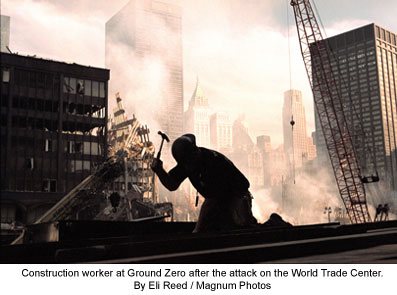

The book New York September 11 by Magnum Photographers is available for sale for $30.00.

The book New York September 11 by Magnum Photographers is available for sale for $30.00.

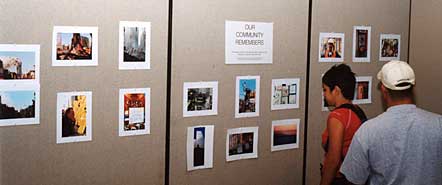

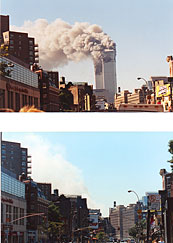

OUT OF A CLEAR BLUE SKY is an exhibition to commemorate the first anniversary of the tragedy of September 11. This photographic exhibit includes images by Magnum photographers from the book

OUT OF A CLEAR BLUE SKY is an exhibition to commemorate the first anniversary of the tragedy of September 11. This photographic exhibit includes images by Magnum photographers from the book

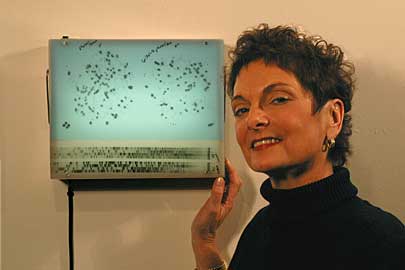

here is new york is not a conventional gallery show. It is something new, a show tailored to the nature of the event, and to the response it has elicited. The exhibition is subtitled "A Democracy of Photographs" because anyone and everyone who has taken pictures relating to the tragedy is invited to bring or ftp their images to the gallery (in SOHO) , where they will be digitally scanned, archivally printed and displayed on the walls alongside the work of top photojournalists and other professional photographers.

here is new york is not a conventional gallery show. It is something new, a show tailored to the nature of the event, and to the response it has elicited. The exhibition is subtitled "A Democracy of Photographs" because anyone and everyone who has taken pictures relating to the tragedy is invited to bring or ftp their images to the gallery (in SOHO) , where they will be digitally scanned, archivally printed and displayed on the walls alongside the work of top photojournalists and other professional photographers.

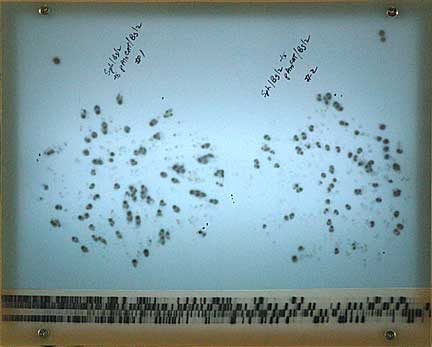

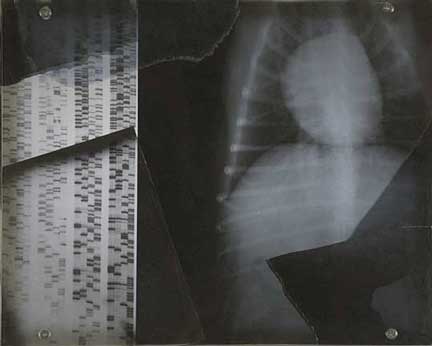

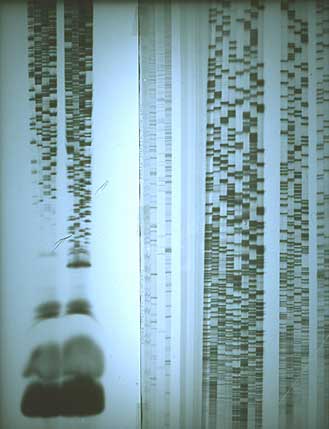

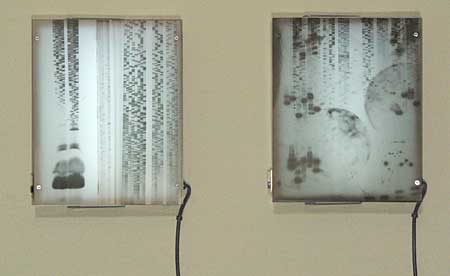

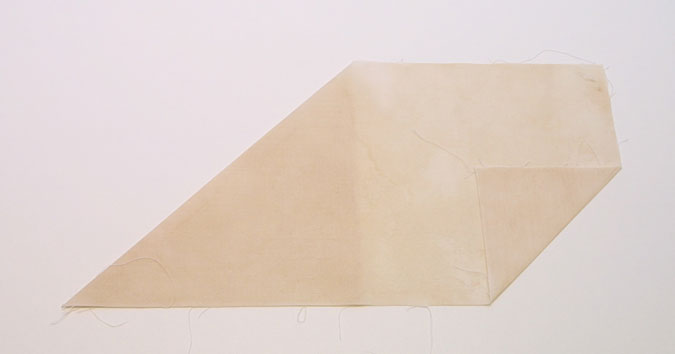

Grain

by Janet Passehl

Grain

by Janet Passehl

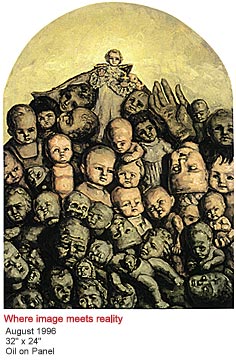

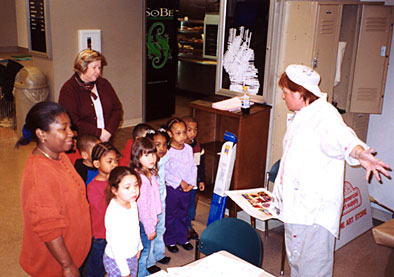

Artistically, I transform discarded objects to create a visual language that evokes the experiences of impermanence and loss, fragility and vulnerability, pain and most of all, healing and survival. This work has evolved from my experiences with the homeless and other marginalized communities.

Artistically, I transform discarded objects to create a visual language that evokes the experiences of impermanence and loss, fragility and vulnerability, pain and most of all, healing and survival. This work has evolved from my experiences with the homeless and other marginalized communities.