Of Woman Born

“There is nothing revolutionary whatsoever about the control of women’s bodies by men,” to quote author, poet and feminist, Adrienne Rich. “The woman’s body is the terrain on which patriarchy is erected.” Of Woman Born explores the ways in which male dominance has manifested itself in familial, social, legal, political, religious and economic systems—patriarchal structures that, over the centuries, have continually been used to dominate, oppress and exploit women.

Although women have made great strides, such as the right to vote and equal access to education, there is still more work to be done. Women’s rights are human rights and include freedom from discrimination, freedom from violence, and freedom from gender inequality.

-

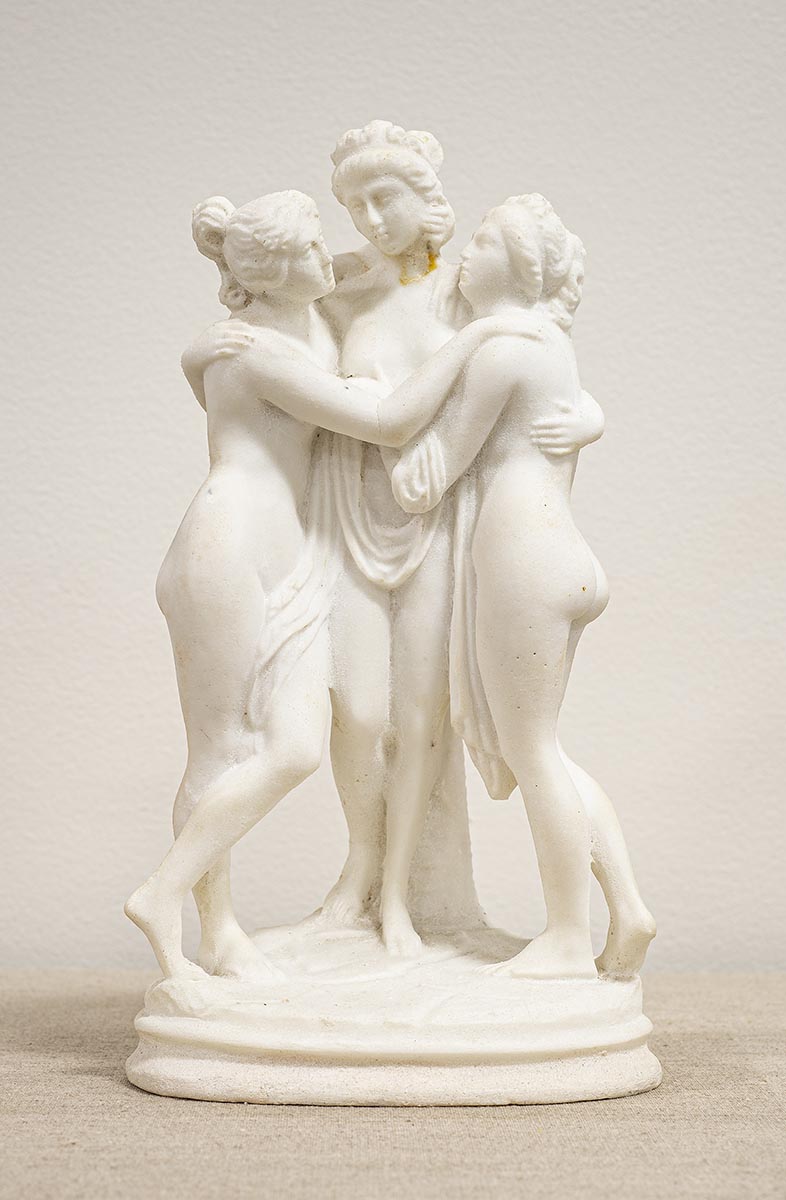

Antonio Canova

Italian, 1757-1822

The Three Graces, 19th century

10 x 4.5 x 3”

Cast alabaster

2009.23.132

Gift of Jud and Barrie Ebersma

The nudes of ancient Greece and Rome came to influence later Western art, and to define what was considered beautiful. The values and ideals of the Greco-Roman culture were defined by perfection in form: unity, harmony and symmetry. Art historian, Kenneth Clark, considered “idealization to be the hallmark of true nudes, as opposed to more descriptive and less artful figures that he considered merely naked. His emphasis on idealization points to an essential issue: seductive and appealing as nudes in art may be, they are meant to stir the mind as well as the passions.” 1

The Three Graces, seen here, is a reproduction of one of the most famous Neoclassical masterpieces by the renowned Italian sculptor, Antonio Canova. Inspired by the sculptures of Ancient Greece and Rome, he revived their aesthetic ideals of symmetry, proportion and balance of form. This work depicts the daughters of Zeus, from left to right, Euphrosyne, Aglaea and Thalia, who represent radiance, joy, and youth and beauty, respectively.

These goddesses of nature formed the original mythology of the early Greeks and, over time, evolved into The Three Graces. As companions of Aphrodite: Goddess of Love and Beauty, they confer beauty and enjoyment in all its forms, from physical to intellectual, to artistic and moral and, as attendants to the Muses, they are associated with the most perfect works of art.

-

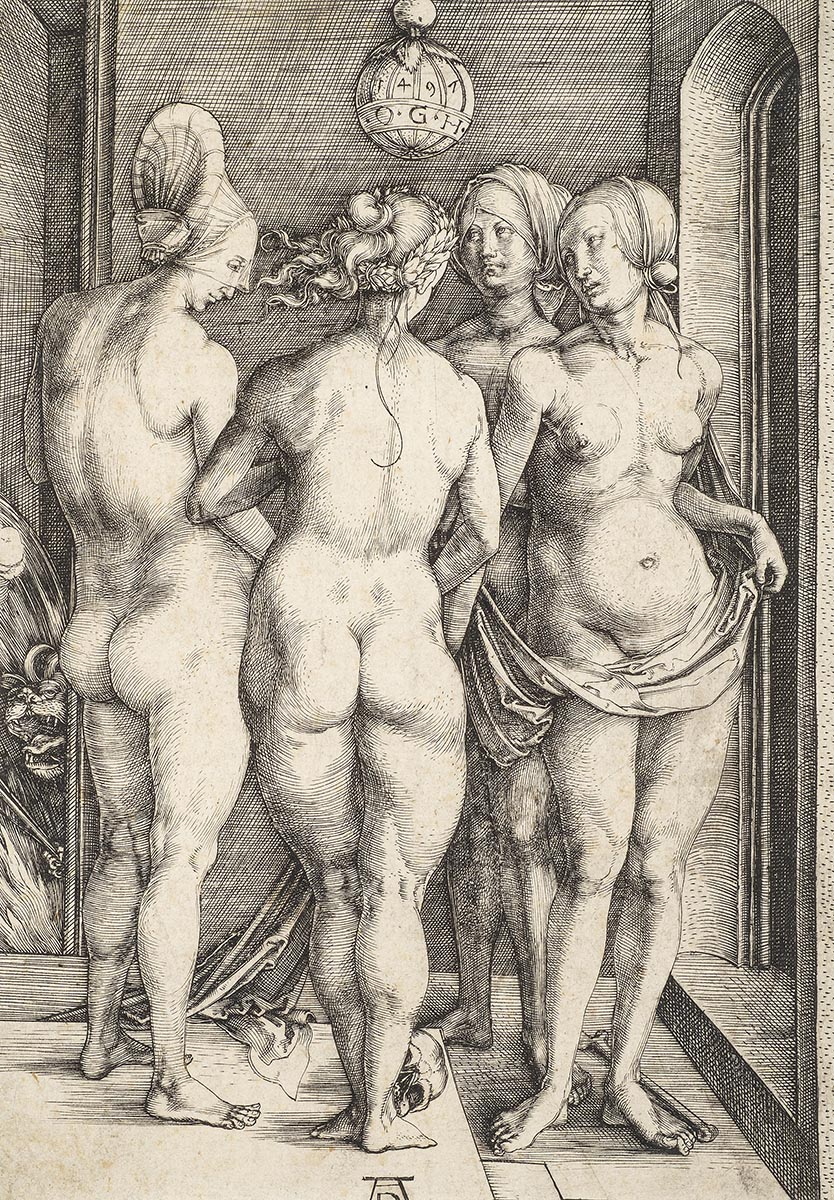

Albrecht Dürer

German, 1471-1528

Untitled (The Four Witches or The Judgement of Paris), 1497

20.25 x 16.25”

Engraving

1976.02.01

Gift of Stanley Manasevit

Regarded as the greatest German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer’s immense body of work includes altarpieces and religious works, numerous portraits and self-portraits, and engravings. Here we see his depiction of four nude females along with a skull and long bone on the floor of the chamber while Satan peers through an opening, surreptitiously observing them. Like Canova, Dürer may have been inspired by the famous sculpture, The Three Graces, adopting the composition but instead depicting the Greek goddess Hecate: Guardian of the Household and Patroness of Witchcraft. Often represented with three faces or bodies, it suggests that she is able see into the future, the past and the present. Once revered as a “virgin” goddess, Hecate eschewed marriage, valuing her solitude and independence and, over time, was transformed into a wizened hag or witch.

Perhaps this subject appealed to Dürer when, in fifteenth-century Germany, women were singled out as witches for the first time in history. Witch-hunts swept across the Holy Roman Empire from 1435 to 1750 fueled by the publication of the manual, Malleus Maleficarum, or Hammer of Witches in 1487 inciting mass hysteria in Germany and across Europe. Authored by the priest, Heinrich Kramer, the text was so flawed that the Catholic Church rejected it, stating it did not reflect its teachings. Nevertheless, the publication soon gained in popularity, providing methods for identifying witches as well as providing the Biblical and legal grounds for persecution. The Protestant Reformation of 1517 sparked a religious war with the Holy Roman Empire resulting in tens of thousands of victims who were tried, tortured, and executed, three-quarters of whom were women, resulting in what can rightly be called gendercide.*

* Gendercide is the killing of a specific gender group. Through most of history, girls and women have been the most common victims. Gendercide has three forms: feticide, infanticide, and gender-based violence.

-

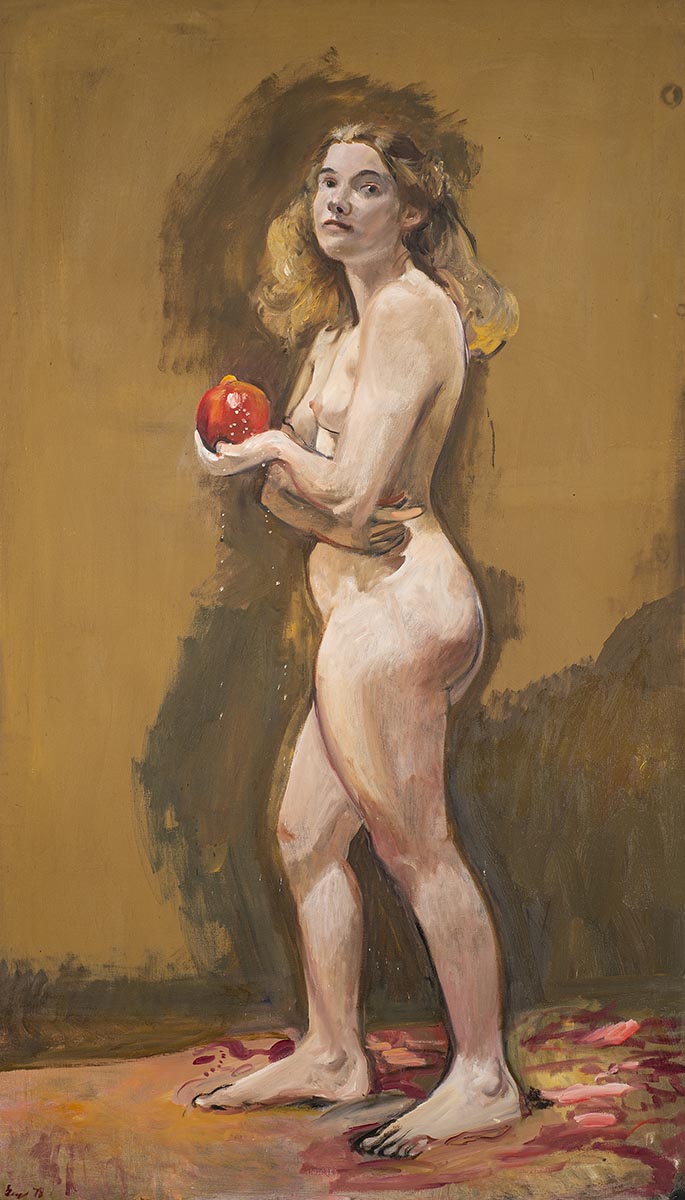

Paul Georges

American, 1948

Eve (Standing Nude), 1978

83 x 49”

Oil canvas

2004.11.01

Gift of Dr. Arthur Ashma

Patriarchy, from the ancient Greek patriarches, is a society where power and privilege are wielded by one gender: Male. The human construct of absolute authority over women is reinforced through religious myths that illustrate that female subservience to man is a God-given condition—and of her own making!

The Greek writer Hesiod, offers an account of the origin of the world in his poem, Theogony, informing us that Zeus created the first woman in order to torment men. She is described as a “beautiful evil and a…deception, which men cannot manage; from her come generations of women, a great pain for mortal men on earth … an evil for mortals, companions in harsh suffering."1 The Greek philosopher Aristotle, in Politics, continues this line of reasoning when he asserts that perfection in spirit and form are realized in the male body, while women are conceived by defective seed. Women, he thought, were foolish, mentally weak, unintelligent and captive to their passions.2

Greek texts and thought appear to be reflected in the Biblical story of the “fall of man” that similarly places the blame for all human suffering squarely at the feet of the first woman, Eve. At the moment God creates her from Adam’s rib, Eve is positioned as less than, inferior, the ‘second sex’ as it were, perennially justifying her subordinate role within both marriage and society. The notion that Eve is deficient and imperfect, incapable of knowing right from wrong, and easily led astray is revealed by her encounter with the Serpent in the Garden of Eden. Disobeying God’s command to eat from any tree except the fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, both Adam and Eve incur his wrath:

To the woman he said, “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” And to Adam he said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

Eve’s enduring reputation as a temptress and thus, a treacherous woman, ensures her everlasting purpose as a symbol of women’s long struggle to overcome patriarchal ideology as expressed through its social, sexual, religious, political and economic power structures.

1 Lefkowitz, Mary. Greek Gods, Human Lives. Yale University Press, 2003 pp. 580-602.

-

Isis and Horus

664–30 B.C.

Late Period–Ptolemaic Period

8.25 x 1.75 x 2.5”

Bronze

1993.24.07

Gift of Herman Klarsfeld

At the dawn of religion God was a woman,1 according to sculptor and art historian, Merlin Stone. Fetish objects, dating from the Upper Paleolithic era through to the Neolithic period, were symbols of fertility that emphasized female attributes—breasts and buttocks—and were carried as a totem or worshipped as a mother goddess, the creator and sustainer of life.2 Proto-Indo-European invaders, it is theorized, supplanted these matriarchal and more egalitarian societies with patriarchal religions and laws.

After the Neolithic Revolution, when humans transitioned from nomadic hunter/gatherers to farming settlements, more complex beliefs, rituals and cult worship emerged. In Egypt, the Goddess Isis, seen here, was often represented as a beautiful woman wearing a sheath dress, seated on a throne and wearing a solar disk and cow horns on her head. She had limitless powers: separating the heavens from earth, healing the sick, and resurrecting the dead. Eventually her attributes and abilities were absorbed into both Greek and Roman mythologies. In Italy, by the end of the 2nd BCE, Isis was worshipped as a “supreme goddess” revered for her omnipotence—she was light and dark, night and day, fire and water, life and death, beginning and end.3 Throughout the Holy Roman Empire, which stretched from England to Egypt, Isis was championed as a symbol of equality between the sexes, conferring to women as much authority and respect as that held by men.

Although paganism was eventually banned in Rome, through laws and persecution, Isis remained too popular to suppress. Eventually, Christians incorporated the attributes belonging to Isis-- suffering, mercy and protection—into Mother Mary, along with the traditional Roman ideals of virginity, devotion and marriage. The concept of death and resurrection had long been established through the myth of Osiris, murdered husband of Isis, and was now made manifest in the figure of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. In time, epithets reserved for Isis such as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven were also ascribed to the Virgin Mary. The image of Isis nursing her miraculously conceived child-god, Horus, likely inspired the conventional Christian iconography of the Madonna with Christ child, also seen here.4

1 Stone, Merlin. When God Was A Woman. New York: The Dial Press, 1975

2 Feminist scholars assert that the Mother Goddess hypothesis remains highly debated and controversial.

3 Pomeroy, Sara B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1976, p. 218.

4 “During the persecutions of the Christians it became relatively commonplace for statues of the Madonna and Child to be disguised as Isis mothering Horus. Many Christians would even publicly follow the cult of Isis as a convenient alibi for their hidden faith. When Christianity eventually became the official religion of the Roman Empire the cult of Isis had already become synonymous with the cult of the Virgin Mary. As pagan worship gradually became outlawed the cult of Isis managed to survive by providing the template for the cult of the Virgin.” https://thedailybeagle.net/2013/04/05/373/

-

Madonna and Child

n.d.

Anonymous

18.5 x 14.5”

Oil on leather

1973.23.14

Gift of Herman Klarsfeld

At the dawn of religion God was a woman,1 according to sculptor and art historian, Merlin Stone. Fetish objects, dating from the Upper Paleolithic era through to the Neolithic period, were symbols of fertility that emphasized female attributes—breasts and buttocks—and were carried as a totem or worshipped as a mother goddess, the creator and sustainer of life.2 Proto-Indo-European invaders, it is theorized, supplanted these matriarchal and more egalitarian societies with patriarchal religions and laws.

After the Neolithic Revolution, when humans transitioned from nomadic hunter/gatherers to farming settlements, more complex beliefs, rituals and cult worship emerged. In Egypt, the Goddess Isis, seen here, was often represented as a beautiful woman wearing a sheath dress, seated on a throne and wearing a solar disk and cow horns on her head. She had limitless powers: separating the heavens from earth, healing the sick, and resurrecting the dead. Eventually her attributes and abilities were absorbed into both Greek and Roman mythologies. In Italy, by the end of the 2nd BCE, Isis was worshipped as a “supreme goddess” revered for her omnipotence—she was light and dark, night and day, fire and water, life and death, beginning and end.3 Throughout the Holy Roman Empire, which stretched from England to Egypt, Isis was championed as a symbol of equality between the sexes, conferring to women as much authority and respect as that held by men.

Although paganism was eventually banned in Rome, through laws and persecution, Isis remained too popular to suppress. Eventually, Christians incorporated the attributes belonging to Isis-- suffering, mercy and protection—into Mother Mary, along with the traditional Roman ideals of virginity, devotion and marriage. The concept of death and resurrection had long been established through the myth of Osiris, murdered husband of Isis, and was now made manifest in the figure of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. In time, epithets reserved for Isis such as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven were also ascribed to the Virgin Mary. The image of Isis nursing her miraculously conceived child-god, Horus, likely inspired the conventional Christian iconography of the Madonna with Christ child, also seen here.4

1 Stone, Merlin. When God Was A Woman. New York: The Dial Press, 1975

2 Feminist scholars assert that the Mother Goddess hypothesis remains highly debated and controversial.

3 Pomeroy, Sara B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1976, p. 218.

4 “During the persecutions of the Christians it became relatively commonplace for statues of the Madonna and Child to be disguised as Isis mothering Horus. Many Christians would even publicly follow the cult of Isis as a convenient alibi for their hidden faith. When Christianity eventually became the official religion of the Roman Empire the cult of Isis had already become synonymous with the cult of the Virgin Mary. As pagan worship gradually became outlawed the cult of Isis managed to survive by providing the template for the cult of the Virgin.” https://thedailybeagle.net/2013/04/05/373/

-

Francisco Zuniga

Mexican, 1912-1998

Maternity, II/III, 1960

66 x 20 x 20”

Bronze

1982.11.01

From the Paleolithic age through to the Neolithic era, infanticide was widely practiced with anthropologists estimating that anywhere from fifteen to fifty percent of newborns were killed to limit the population. A Nomadic lifestyle meant that women could not manage, feed or travel with several small children at once. After the Agricultural Revolution, women’s lives were more rooted, with food supplies steady and more predictable, which led to a “Neolithic baby boom”1 where children were necessary and would eventually provide much needed labor.

Motherhood was the primary occupation of Greco-Roman women regardless of their social class. Children produced in these marriages were the property of the father with male children valued above female children. These warrior cultures required future soldiers to maintain the Empire, and in Greece, generally one female child per family was often all that was needed. Frail, sickly or deformed male babies as well as unwelcome female newborns were abandoned and often succumbed to exposure unless they were adopted into brothels or sold into slavery.2 In Rome, newborns were placed in clay pots and left outside the home to either suffocate, starve or be collected and sold. During the Greco-Roman period, Egyptians, whose culture forbade infanticide and valued both sexes equally, rescued these babies and kept them as household slaves.

Wealthy women had long outsourced the work of nursing and caring for newborns to the working-class. In 1834, England enacted the New Poor Laws, which included the Bastardy Clause, that barred unwed mothers and their illegitimate children from receiving public assistance. Under this new system, men were no longer required to marry the mothers of their children or to provide financial support. These “fallen women” were often turned out of their family homes and, if they were lucky enough to find work, were immediately discharged as soon as their condition became obvious. The shame and sin, as well as the cost to support herself and her child, were borne by the woman alone. For these stigmatized women, leaving their children in the care of foster mothers was often the only option. This practice, called “baby-farming,” was a euphemism for infanticide, an industry that delivered desperate mothers from a life of misery.

Maternity is both a biological state and a cultural construct, and consequently the ideas and expectations surrounding it are often naturalized, making the politics involved in this social role obscure. Feminist poet Adrienne Rich points out the hypocrisy underpinning the notion of absolute respect for human life. She says, “Women know firsthand about the violence of the warrior...[and] the institutional violence of political and social systems in which we have little part, but which affects our bodies and our children… the violence over which we have been told is the way of the world…”3

-

Michael Stone

American, 1945

Mothers and Sons, 4/25, 2008

12 x 16”

Hahnemuhle Photo Rag

308 gsm Epson 7800 printer2017.15.37

Gift of The Museum Project

From the Paleolithic age through to the Neolithic era, infanticide was widely practiced with anthropologists estimating that anywhere from fifteen to fifty percent of newborns were killed to limit the population. A Nomadic lifestyle meant that women could not manage, feed or travel with several small children at once. After the Agricultural Revolution, women’s lives were more rooted, with food supplies steady and more predictable, which led to a “Neolithic baby boom”1 where children were necessary and would eventually provide much needed labor.

Motherhood was the primary occupation of Greco-Roman women regardless of their social class. Children produced in these marriages were the property of the father with male children valued above female children. These warrior cultures required future soldiers to maintain the Empire, and in Greece, generally one female child per family was often all that was needed. Frail, sickly or deformed male babies as well as unwelcome female newborns were abandoned and often succumbed to exposure unless they were adopted into brothels or sold into slavery.2 In Rome, newborns were placed in clay pots and left outside the home to either suffocate, starve or be collected and sold. During the Greco-Roman period, Egyptians, whose culture forbade infanticide and valued both sexes equally, rescued these babies and kept them as household slaves.

Wealthy women had long outsourced the work of nursing and caring for newborns to the working-class. In 1834, England enacted the New Poor Laws, which included the Bastardy Clause, that barred unwed mothers and their illegitimate children from receiving public assistance. Under this new system, men were no longer required to marry the mothers of their children or to provide financial support. These “fallen women” were often turned out of their family homes and, if they were lucky enough to find work, were immediately discharged as soon as their condition became obvious. The shame and sin, as well as the cost to support herself and her child, were borne by the woman alone. For these stigmatized women, leaving their children in the care of foster mothers was often the only option. This practice, called “baby-farming,” was a euphemism for infanticide, an industry that delivered desperate mothers from a life of misery.

Maternity is both a biological state and a cultural construct, and consequently the ideas and expectations surrounding it are often naturalized, making the politics involved in this social role obscure. Feminist poet Adrienne Rich points out the hypocrisy underpinning the notion of absolute respect for human life. She says, “Women know firsthand about the violence of the warrior...[and] the institutional violence of political and social systems in which we have little part, but which affects our bodies and our children… the violence over which we have been told is the way of the world…”3

-

Sante Graziani

American, 1920-2005

Three Identical Women, Three Identical Children, 58/90

46 x 51”

Lithograph on cream paper

1994.05.01

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burt Chernow

A woman’s place is in the home, a well-worn phrase that can be traced back to the Greek playwright Aeschylus in 467 BCE, was popularized in 19th century books, church sermons and magazines, like Godey’s Lady’s Book and Ladies’ Companion, that espoused the Victorian ideals of the “The Cult of Domesticity.” The “angel in the house” was the embodiment of Purity, Piety, Submissiveness and Domesticity, a set of beliefs that essentially confined a woman to the private sphere of home and hearth.

The “true woman,” as she was also called, was charged with the care of the home, overseeing the formal and religious education of the children, and above all, provided a haven for her harried husband from the rough and tumble world. Upper and middle-class women were not permitted to work outside the home, according to historian Barbara Welter, as they were seen as too delicate of mind and body to withstand the demands of the public sphere.

The high-status female, barred from the labor market, also communicated to Victorian society that her husband was successful and wealthy, thus able to keep her. Of course, these privileges did not extend to the working class, poor, or women of color who, without a private income or a man, were not only employed outside the home but were seen by Victorian society as immoral, unworthy and contemptible.

Although the Cult of Domesticity restricted women’s options for work, for education, and participation in the arenas of politics, business, and public service, it nevertheless provided women with the leisure time to network, organize and advocate for reform from within the home. Wealthy, well-educated and well-connected women like Catherine Beecher, who spear-headed the first protest led by women against the Indian Removal Act, and her sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, a world-renowned author who used her notoriety and influence to advocate on behalf of the anti-slavery movement are such examples.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the writers and philosophers Mary Wollstonecraft, Frances Wright, and Harriet Martineau were criticized by clergy and the press for advocating for women’s rights and calling for social equality which was seen as undermining the feminine virtues of passivity and submission promoted by the Cult of Domesticity. After voting rights were expanded to include almost all white males between 1812 to 1850, many women took encouragement believing that they, too, might win the right to vote. In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the Seneca Falls Convention, held in New York, which was the the first women’s rights movement focusing on women's suffrage, political activism, and legal independence. Modeled on the Declaration of Independence, Stanton read from her own document, the Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights…

On that July day, Stanton’s call to action sparked the beginning of the fight for equal rights for women in America.

i Welter, Barbara (1966). “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly, p. 151-174

-

Suzanne Benton

American, 1936

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (from the Votes for Women series), 1996

36 x 28”

Monoprint with Chine Colle on Cream paper

2006.09.01

Housatonic Museum of Art Purchase

The women’s movement included a decades long fight for the right to vote that began in the mid-19th century. The Seneca Falls convention in July of 1848, brought together two hundred women and forty men, including feminists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, to fight for the right to vote. The delegates believed women to be full citizens and not restricted to their roles as wives or mothers. The claustrophobia of the cult of domesticity gave way to activism when intrepid, outspoken women campaigned to reform societal ills as diverse as prostitution, alcohol and, most significantly, slavery. 1

Feminist artist Suzanne Benton, of Ridgefield, dedicated herself to researching and documenting influential suffragettes in her print series Votes for Women. The top print is of Antoinette Brown Blackwell who graduated Oberlin College in Ohio in 1847 and was the first ordained Protestant minister in the United States. Blackwell joined the women’s rights movement giving her first speech at the 1850 National Women’s Rights Convention. Also active in the abolitionist and temperance movements she wrote for Frederick Douglass’ newspaper, The North Star. In 1873, Blackwell founded the Association for the Advancement of Women and, in 1920 at age 95, she witnessed the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution giving women the right to vote.

1 https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/seneca-falls-convention-begins

-

Suzanne Benton

American, 1936

Florence Hope Luscomb (from the Votes for Women series), 1991

36 x 28”

Monoprint with Chine Colle on Cream paper

2005.02.01

Gift of Vivien Leone

The second print features Florence Hope Luscomb, one of the first women to graduate MIT and receive her degree in Architecture in 1909. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1887, Luscomb’s mother, Hannah Knox Luscomb, was a feminist and active in the women’s suffrage movement. When she was only five, her mother brought her to hear Susan B. Anthony, the social reformer and women’s rights activist speak, igniting within her a life-long passion for advocacy work. After nine years as an architect, Luscomb left the field to work full-time on behalf of the Boston Equal Suffrage Association. And while women’s history remembers the names of Blackwell and Luscomb, let us not forget the countless extraordinary women, Black and White, whose contributions remain anonymous.

-

Nicolas Africano

American, 1948

Ironing Board (Battered Woman Series), 1978

85 x 65”

Oil Acrylic and wax crayons on canvas

2001.01.01

Gift of Dr. Donald Dworken

Ironing her shirt, a woman is preparing to face the day. As we look more closely at the tiny isolated figure floating in a sea of pink, we spot bruises on her face and back. The notion of home as a safe haven is upended, instead it becomes a private space in which to exercise gender-based violence.

In 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a landmark piece of legislation designed to support and protect survivors of domestic violence, stalking, and sexual assault, was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. Issues, such as domestic abuse, moved out of the familial, private sphere to become a community issue. In 2019, the reauthorization of VAWA passed the House of Representatives before stopping at the Republican controlled Senate. Although Congress has continued to provide funding grants for programs to address domestic violence and the Office of Violence Against Women remains active in the U.S. Justice Department, the future of safety and equality for women once again hangs in the balance.

-

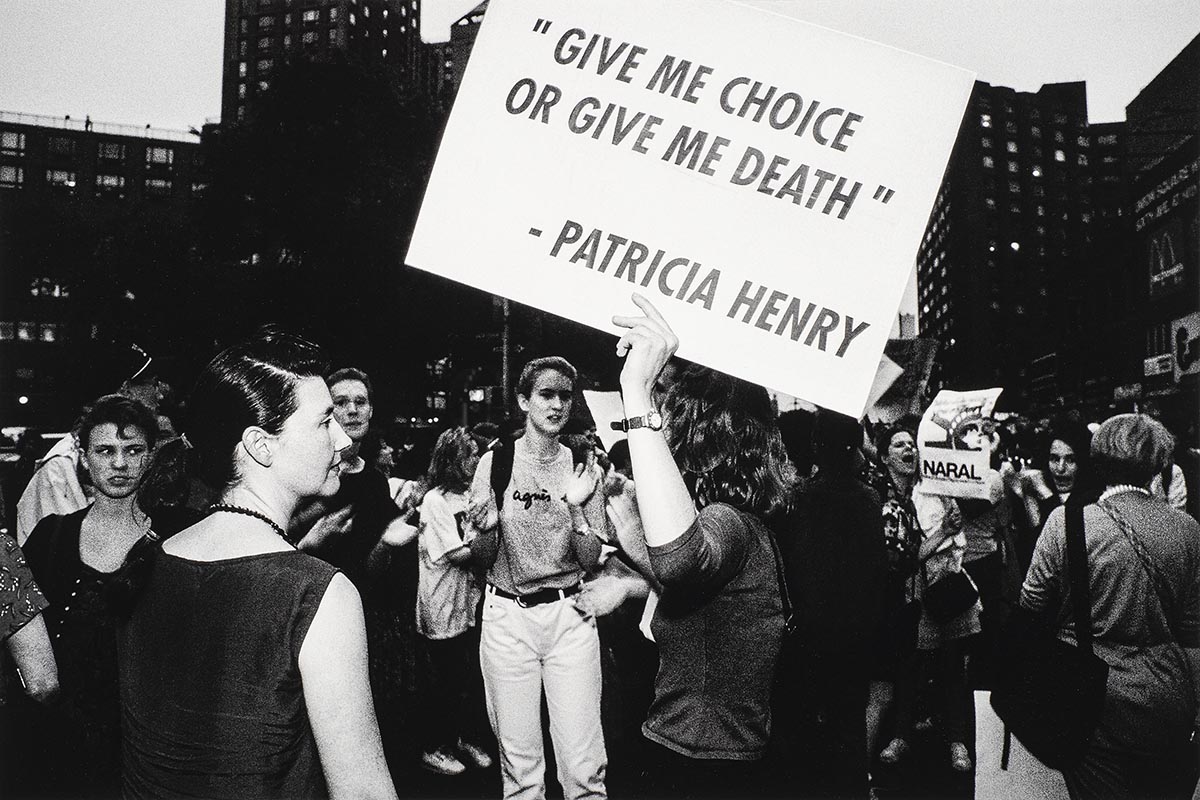

Donna Ferrato

American, 1949

Choice Aint No Joke, Union Square, N.Y.C., 1989

24 x 30”

Archival pigment print

2019.15.08

Gift of Chris Campbell

Abortion has been practiced since ancient times including techniques such as binding, use of abortifacients and, of course, the use of instruments. The Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, dated 1550 BCE, offers the first written documentation of an induced abortion. In Ancient Greece and Rome it is hard to imagine that a culture that practiced infanticide would outlaw abortion, and there was one exception: A wife was obligated to carry a child to term if her husband died in order that the male child could inherit his estate.1

For most of history, women were able to terminate a pregnancy prior to the moment of quickening, that is, when she could feel the movement of her child. In Colonial America, the same laws existed for both married and unmarried women, allowing them to determine when, if and how many children to bear. By the 19th century, as Victorian women began to limit the number of children they bore, waves of immigrants began arriving on the shores of America threatening the status quo of the ruling class: white Anglo-Saxon Protestant males. The response to family planning was swift, according to Carroll Smith-Rosenberg in her book Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America, with the Victorian anti-abortion movement portraying women who terminated their pregnancies as unnatural and selfish, undermining the expected, patriotic, and godly role of the American woman—that of wife and mother. 2

By the 1960s during the civil rights and women’s liberation movement, women once again sought to manage their own bodies. In 1973, the Supreme Court handed down the landmark decision of Roe v Wade stating that abortion is a woman’s constitutional right, along with control of her own reproductive health. Forty-eight years later, as the white population recedes in number, efforts to overturn Roe v. Wade are gaining momentum through Republican controlled State legislatures that are seeking to restrict access to abortion clinics or to ban it altogether.

-

Donna Ferrato

American, 1949

Operation Rescue, Wash., D.C., 1992 (Pro Birth Activist at Pro Choice Rally)

24 x 30”

Archival pigment print

2019.15.07

Gift of Chris Campbell

Abortion has been practiced since ancient times including techniques such as binding, use of abortifacients and, of course, the use of instruments. The Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, dated 1550 BCE, offers the first written documentation of an induced abortion. In Ancient Greece and Rome it is hard to imagine that a culture that practiced infanticide would outlaw abortion, and there was one exception: A wife was obligated to carry a child to term if her husband died in order that the male child could inherit his estate.1

For most of history, women were able to terminate a pregnancy prior to the moment of quickening, that is, when she could feel the movement of her child. In Colonial America, the same laws existed for both married and unmarried women, allowing them to determine when, if and how many children to bear. By the 19th century, as Victorian women began to limit the number of children they bore, waves of immigrants began arriving on the shores of America threatening the status quo of the ruling class: white Anglo-Saxon Protestant males. The response to family planning was swift, according to Carroll Smith-Rosenberg in her book Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America, with the Victorian anti-abortion movement portraying women who terminated their pregnancies as unnatural and selfish, undermining the expected, patriotic, and godly role of the American woman—that of wife and mother. 2

By the 1960s during the civil rights and women’s liberation movement, women once again sought to manage their own bodies. In 1973, the Supreme Court handed down the landmark decision of Roe v Wade stating that abortion is a woman’s constitutional right, along with control of her own reproductive health. Forty-eight years later, as the white population recedes in number, efforts to overturn Roe v. Wade are gaining momentum through Republican controlled State legislatures that are seeking to restrict access to abortion clinics or to ban it altogether.

-

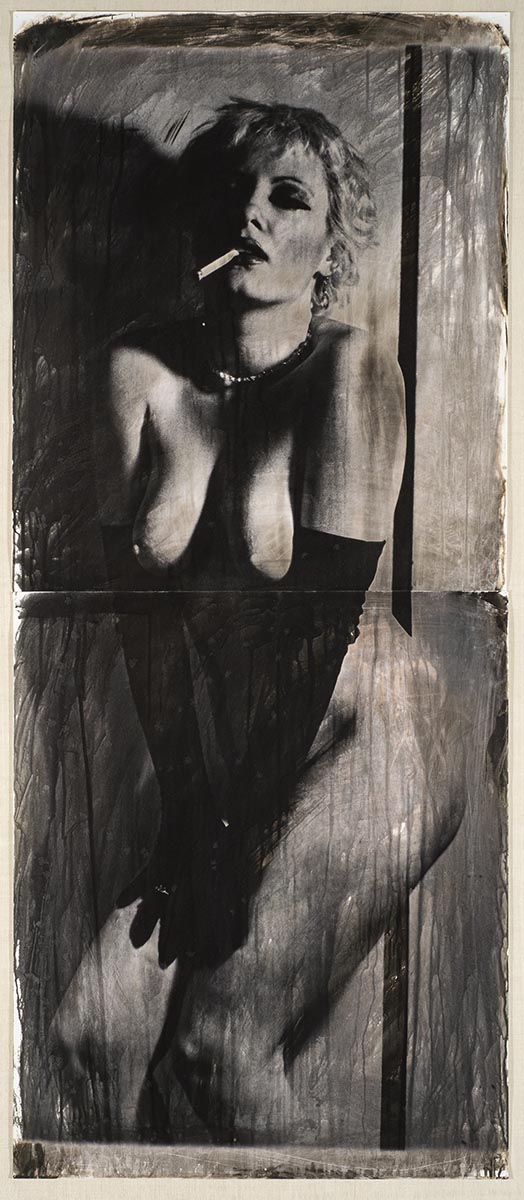

Lynne Augeri

American, 1956

Bated Breath, 1987

55 x 25”

Monotype and photograph

1996.05.02

Gift of Lee Goldstein

Erotica is a genre of art that spans thousands of years and can be found across many cultures. For women in the Victorian Age, domestic purity and feminine virtue were the ideals that informed “true womanhood,” with sex strictly reserved for procreation. Yet, for all their rigid morality codes and high-minded principles, the literature and theater of the day revealed their obsession with sex. In 1839, the invention of photography was quickly put to use creating illicit images for both the hetero and homosexual “underground market” that catered to the upper and lower classes alike.

Lynne Augeri’s photographic self-portraits take the genre of Victorian daguerreotypes as inspiration, blurring the line between the “artistic and the pornographic, so Augeri’s self-portraits occupy an ambiguous zone between “positive” sexual bravado and “perverse” exhibitionism, confidently laying out the contradictions between the two.” 1 She employs the visual rhetoric of both the ‘erotic’ and the ‘pornographic’ and toys with the traditions of artistic conventions that inform the viewer as to what is and what isn’t an acceptable image. These visual cues, however, are mutable as social mores change across time and what was once unacceptable becomes mainstream. Augeri’s photographs deal specifically with sexist representations of women in art and in popular culture to reveal the “systemic quality of objectification and fetishism in the representation of women … [to show] the complex network of relations that meshes power, patriarchy and representation.” 2

1 John Howell, “Lynne Augeri,” ArtForum, December 1984, page 90.

2 A. Solomon-Godeau, ‘Reconsidering Erotic Photography: Notes for a Project of Historical Salvage’, in A. Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photography – History, Institutions and Practices, Minneapolis, 1991, pp. 236.

-

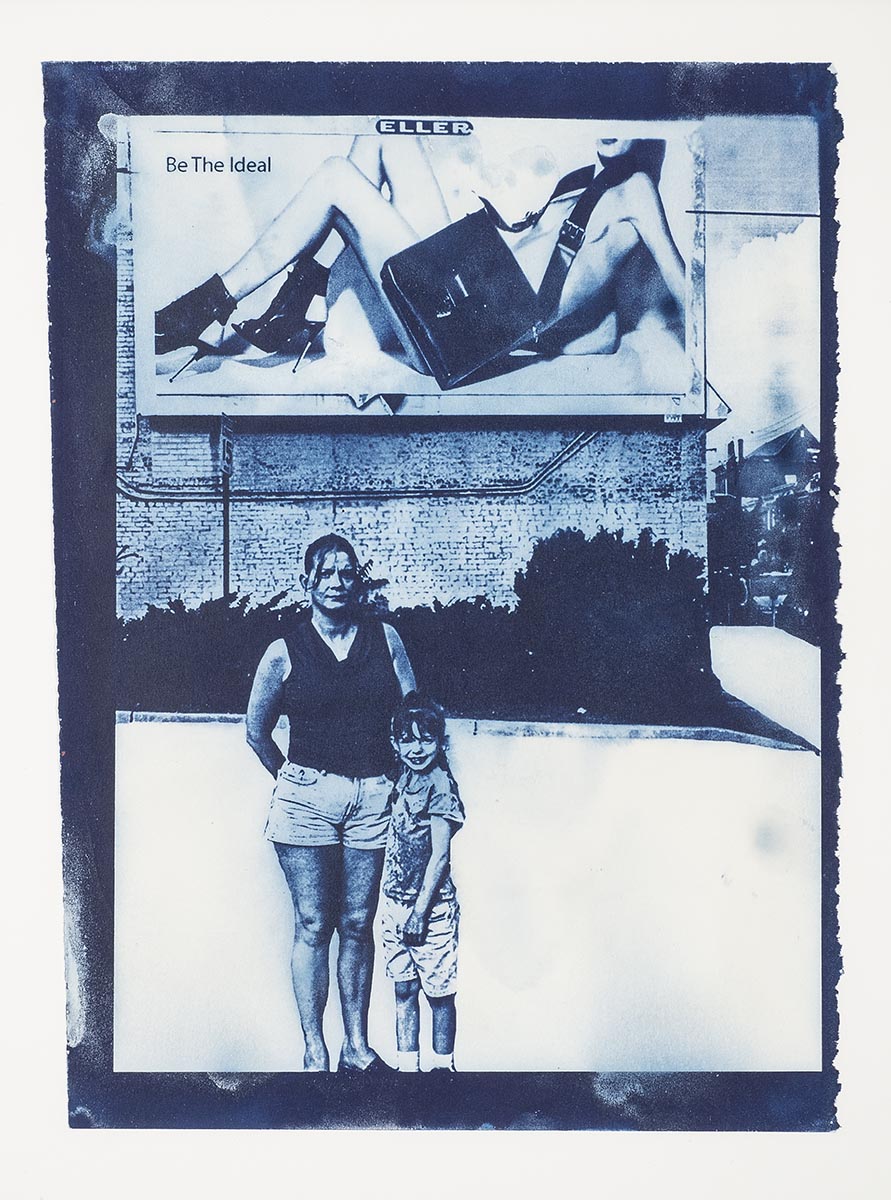

Aidan Boyle

American, 1993

Be the Ideal, 2016

214.5 x 10.5”

Cyanotype

On loan courtesy of the artist

Here, we see an average looking mother and daughter, smiling for the camera against a billboard backdrop featuring a young, hypersexualized, ultra-thin model, completely nude but for the shoes and a strategically placed handbag. Advertising images, like this one, have co-opted the conventions of pornography, a practice that is referred to by several different labels including pornographication, porno chic and pornification. The commodification of the female body performs a normative role culturally and socially as women are sold the aesthetics of porno chic, integrating style elements into the everyday presentation of themselves. Fashion designers, like Tom Ford, claim that these images are empowering, however, they may simply be the latest iteration of the objectification of women..

-

Aidan Boyle

American, 1993

Achieve Perfection Through Dissection, 2016

214.5 x 10.5”

Cyanotype

On loan courtesy of the artist

The media habitually depicts a narrow and often unattainable standard of an ideal physical beauty and links this standard to women’s own attractiveness and value. Repeated exposure to messages that equate beauty and appearance with a female’s self-worth leads to the internalization of impossible cultural standards of beauty which, in turn, may lead to body dissatisfaction, social anxiety, depression, and eating disorders especially in adolescents.

In this work, the artist has employed an advertising technique that uses a fragmented female face presented as a collection of problematic parts in search of a solution while the accompanying text reinforces the same message: perfection can be procured through cosmetics or cosmetic surgery. Boyle’s artwork invites us to examine a media environment that continually objectifies the female body, to question traditional gender norms and to think critically about the relationship between representation and power.

-

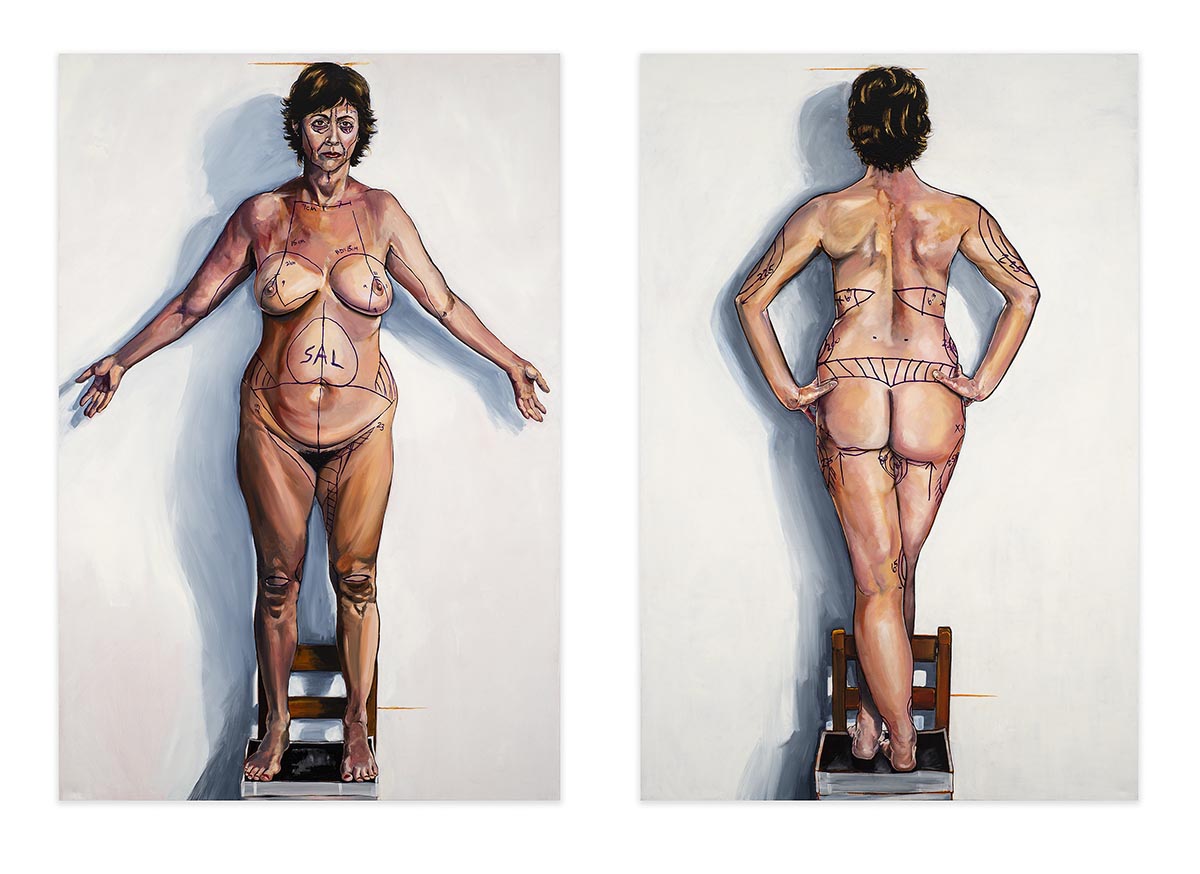

Sherri Wolfgang

American, 1958

Is This God’s Plan, 2012

72 x 48” (diptych)

Oil on canvas

2017.14.01

Using herself as a model, Westport artist Sherri Wolfgang is marked and mapped for a plethora of surgical procedures to tighten and tweak her body and face. Enslaved to the male gaze, a term coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey in her seminal 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, women are often viewed as objects of male desire. Our culture’s emphasis on a woman’s beauty supersedes all her other attributes, credentials and accomplishments. Wolfgang illustrates for the viewer the extreme measures that women will take to slow the aging process in an effort to preserve their status, worth, and security.

-

Lori Petchers

American, 1959

Faith Baum

American, 1952

Forever 21, 2012 (from the Old Bag series), 2014-2015

70 x 35”

Photograph

2015.04.01

The Old Bags Project began in 2011 as a collaboration between two older Fairfield artists in response to a consumer culture that privileges youth. Co-opting the term old bag, a phrase often used to diminish an aging woman’s value, they invited older women to participate in this portrait project which has had a variety of iterations including photographs, as seen here, video and audio installations, outdoor projections and a book. Having understood advertising’s messages-- that growing old is not only unacceptable, it’s offensive-- Petchers and Baum ask us to examine the ways in which advertising coerces women to participate in and internalize the pressure to be forever twenty-one.

-